Obituary

Obituary of Dr. Frederick S. Humphries, Sr

Please share a memory of Dr. Frederick to include in a keepsake book for family and friends.

Frederick S. Humphries, Ph. D: The Entrepreneur of Black Excellence in Higher Education

Dr. Frederick S. Humphries, passed away on June 24, leaving a legacy of Black exceptionalism that remains the envy of academia. The young man from the port town of Apalachicola on the Gulf Coast of Florida would have an extraordinary impact on many thousands of Black students, and their families.

Growing up in Apalachicola, Humphries was influenced by a diverse group of people. He attended Holy Family School, one of the few Black Catholic grammar schools in the south ruled by Black nuns who were relentless disciplinarians. Once, Humphries’ school scored so high on an exam, the Monseigneur suspected cheating. He gave them a different test and their scores were even better. The small town had a reputation for Black high achievers. But Fred Humphries said it was not enough for his high school math teacher Charlie Watson who constantly pushed him to “do better” and to always “strive for excellence.” Construction work in Apalachicola introduced him to Ruffin Rhodes. Ruffin talked incessantly about the power of education. Finally, Humphries said, “What’s the highest degree of educational achievement?” Rhodes said, “a doctorate.”

With that, Humphries was off to Florida A&M College, which became a university during his time there. He was a popular student. Tall, handsome, and smart, known for his competitive spirit on the basketball court and in the classroom. He enjoyed getting better grades than his big-city friends. To his buddy Carl Kirksey from Miami, he asked, “How did you do on that math exam?” Carl said, “I got an 80.” “I got a 95,” was Humphries retort. He graduated with honors with a degree in chemistry, from FAMU. Humphries began his role as a member of the “First Evers” as the first African American to earn a doctorate in physical chemistry from the University of Pittsburgh.

After teaching chemistry at FAMU in 1974, he became president of Tennessee State University, an arch-rival of the Rattlers. Humphries was president when the state wanted to merge TSU with the Nashville campus of the University of Tennessee, a White school. It happened, but the federal land grant status of TSU protected it from a hostile take of sorts by a White institution. Tennessee State maintained its administrative status and brand.

That episode was not Humphries's first bout with suppression. And while he treated institutional racism with indifference, he recognized it as a worthy adversary to be outmaneuvered. That was his approach and it was a successful strategy.

When he returned to his beloved FAMU as president in 1985, it was the beginning of a remarkable journey that would elevate the university and Historically Black Colleges and Universities to their rightful status as valuable institutions of higher learning. Humphries's commanding presence, innovating ideas, and enthusiasm was a powerful magnet attracting students, faculty, corporations, alumni, and research dollars at a level never before realized.

He was defiant and unrelenting when advancing FAMU. Here’s why.

During the Humphries’ years from 1985-2001, FAMU burst onto the scene as an HBCU with academic credentials unmatched. First, he increased enrollment with an unorthodox recruitment style that was legendary. He would approach young people on the streets of Europe and Africa touting the FAMU brand. The universities dominance of National Achievement Scholars would upend academic norms. FAMU led the nation with the scholars outpacing Harvard, Yale, and Stanford in 1992, 95, 97, and tying Harvard in 2000. But, also part of the big picture was Humphries’ commitment to disadvantaged students with untapped potential who would be nurtured at FAMU. That was the Fred Humphries’ dream.

The intrinsic strength of an HBCU education was a powerful weapon for Humphries who's motto Excellence with Caring resonated nationwide. His defiance of racial norms was a startling rebuke to the Board of Regents and all those he viewed as a threat to FAMU. Humphries’ FAMU engendered the kind of can-do spirit and self-esteem the next generation needed to compete in the marketplace.

During his presidency, Frederick Humphries raised over $157 million, awarded 873 Life Gets Better Scholarships, and increased Foundation revenues tenfold. FAMU was named College of the Year by Time Magazine and the Princeton Review. Grants jumped from $8 million to $62 million and enrollment soared from 5,000 -12,000. Humphries was always focused on FAMU's research profile but now was able to strengthen engineering, the sciences, and pre-law. Of course, he successfully restored the FAMU College of Law, in 2000.

The famous 8th FAMU President always credited a great faculty for playing a major role in the success of his efforts. The expansion of graduate studies is a testament to that fact. The most extraordinary part of the Humphries legacy was the elevation of FAMU to prominence that in turn established the relevancy of all Historically Black Colleges and Universities.

Dr. Humphries was proceeded in death by his beloved parents, Thornton G. Humphries and Minnie Henry Humphries; his brother, Thornton G. Humphries and sister, Mona Humphries Bailey. He was married to the late Antoinette McTurner Humphries. He is survived by their three children, Frederick S. Jr., (Kim Sheftall) of Washington, DC; Robin Tanya Humphries Watson of Orlando, Fla.; Laurence Anthony (Carnesha Allen) of Houston, Tx.; and eight grandchildren Brian Alexander Watson of Oakland, Calif., Arielle Simone Humphries of New York, N.Y, Kirsten Antoinette Watson of Los Angeles, Calif.; Frederick S. Humphries, III of Los Angeles Calif., Laurence Anthony Humphries II of Atlanta, Ga., Dylan Gabrielle Humphries of Atlanta, Ga., Isabella Antoinette Humphries of Houston, Tx., and Pierce Henry Humphries, of Houston, Tx.; and two sisters, Mamie (the late Robert) Stevens of Moss Point, Miss.; Barbara (Milton) Jones of Fort Lauderdale, Fla.; two sisters-in-law, Maude (the late Thornton) Humphries of Fort Lauderdale, Fla.; and Consuelo McTurner of Pittsburgh, Penn; a brother-in-law, William Peter (the late Mona Humphries) Bailey of Seattle, WA.; a beloved companion, Barbara Curry Murrell, of Nashville, Tenn.; and a host of dearly loved nieces, nephews, and dear friends.

To send flowers to the family or plant a tree in memory of Dr. Frederick Humphries, Sr, please visit Tribute Store

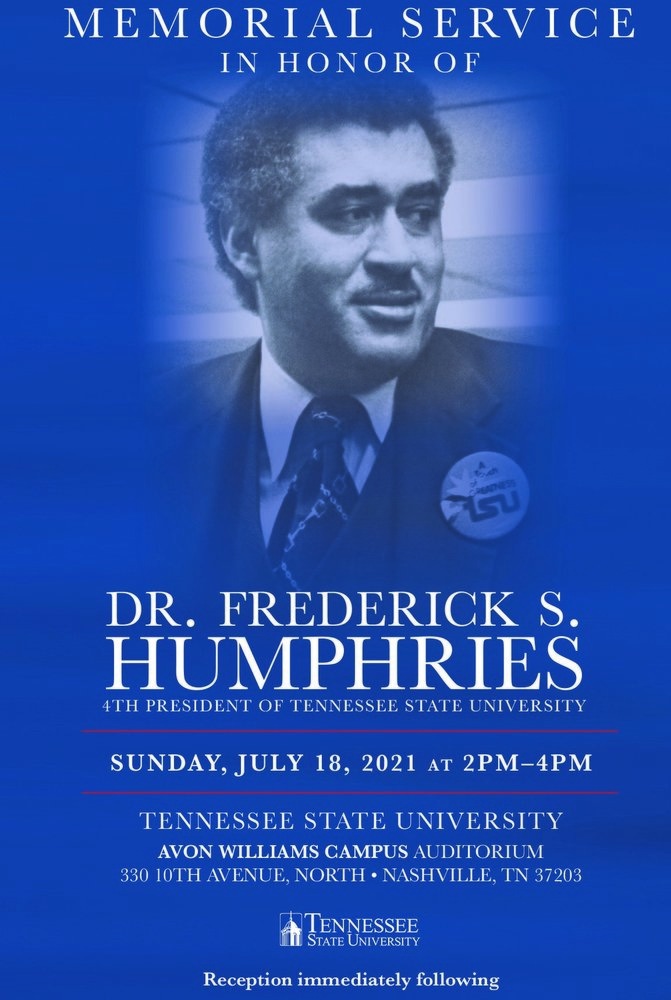

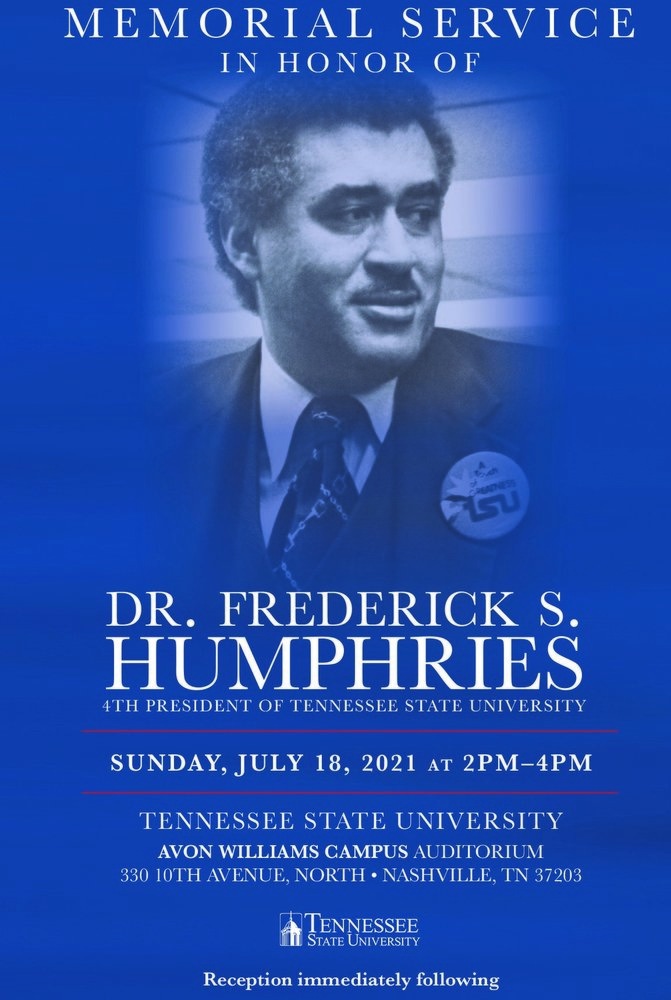

Sunday

18

July

Memorial Service

2:00 pm - 4:00 pm

Sunday, July 18, 2021

Tennessee University University Avon Williams Campus Auditorium

330 10th Avenue North

Nashville, Tennessee, United States

Need Directions?

Online Memory & Photo Sharing Event

Ongoing

Online Event

About this Event

In Loving Memory

Dr. Frederick Humphries, Sr

Thursday, June 24, 2021

Look inside to read what others have shared

Family and friends are coming together online to create a special keepsake. Every memory left on the online obituary will be automatically included in this book.

Share Your Memory of

Dr. Frederick

Be the first to upload a memory!

ABOUT US

Lewis & Wright Funeral Directors strives to help you and your family to achieve peace of mind which is an important part of the healing process. We are pleased to offer grief counseling as a part of our aftercare service.

Our Location

Lewis & Wright Funeral Directors

2500 Clarksville Hwy. Nashville, Tennessee

37208

Phone: (615) 255-2371

Fax: (615) 255-4926

Map

Have A Question?

We are available 24 hours a day, seven days a week to answer questions you may have and provide direction. Please call us directly at (615) 255-2371 if you require immediate assistance.